The creative world is naturally fragmented, a Venn diagram where all paths are inherently related but do not always communicate amongst themselves. The painter and the pianist, the illustrator and the sculptor. This is where artistic endeavors are categorized and assigned, given to the proper audience and markets — the niche, the mainstream, and the forgotten.

My natural lens is through the world of illustration, an artform that is welcomed into the fold of the mainstream, with barely a sliver of overlap into the space of fine art. Historically, illustration is visual storytelling for the illiterate. From the illuminated manuscript and the stained glass of cathedrals to modern murals and the pixel-based pictography of the emoji. All tell the narrative of humanity through a well-crafted and pointed image. For the illustrator, criticism is an everyday occurrence. The client, the art director, the audience. Not every creative endeavor follows this path but each benefits from critical analysis, which can come in various forms. On May 11th, 2018, Pulitzer Prize winning art critic Jerry Saltz posted the following on his Instagram —

From the Instagram feed of art critic Jerry Saltz

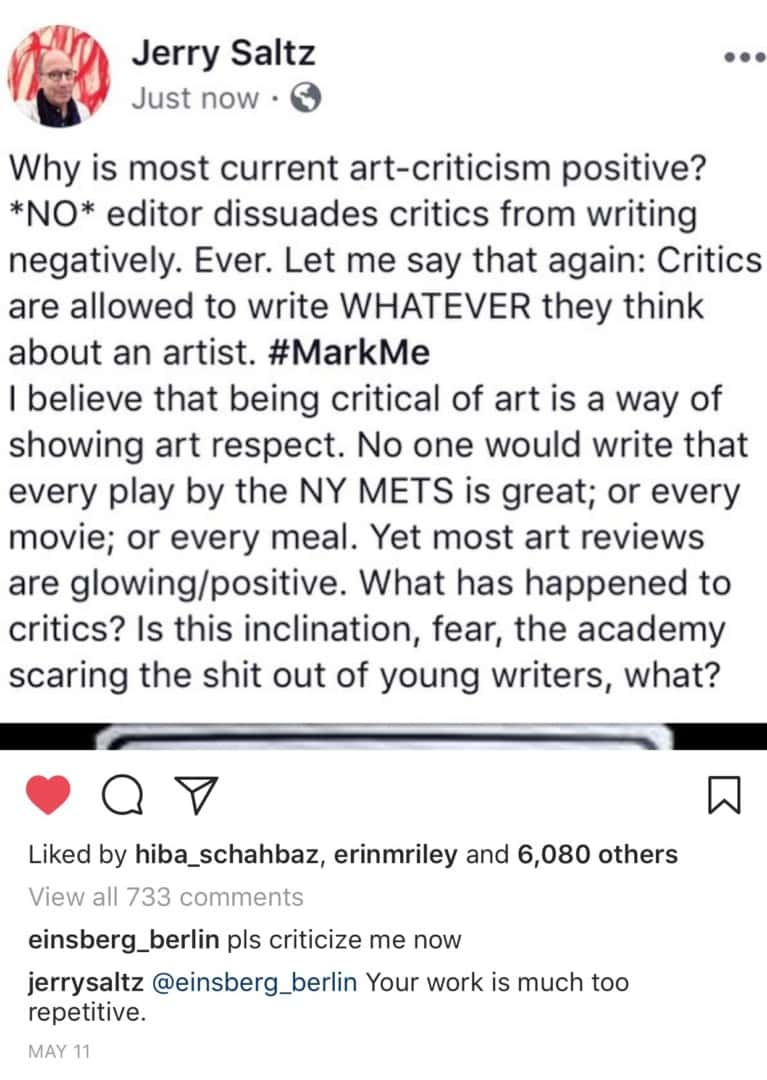

Saltz’s comment is multi-layered and unravels in a series of questions and declarations. It’s about the art, the artist, the audience, and the voice in between. Critic as translator. What’s fascinating about the comment is its take on the relationship between the writer and their subject. The artist does not need the critic as the art will keep coming without comment, but the critic is there as witness — I saw this and these are my thoughts. Without the art to bear witness to, the critic is voiceless. As someone who was paid to criticize the work of others for years, and has also paid for criticisms of my own writing to gain a better grasp on language and narrative, I understand the value of an outsider’s perspective on what it is we put our fullest of selves into. Saltz’s Instagram post garnered 731 comments, but one specifically resonated with me. Artist @einsberg_berlin, asked for their own work to be criticized by Saltz, who obliged.

From the Instagram feed of art critic Jerry Saltz

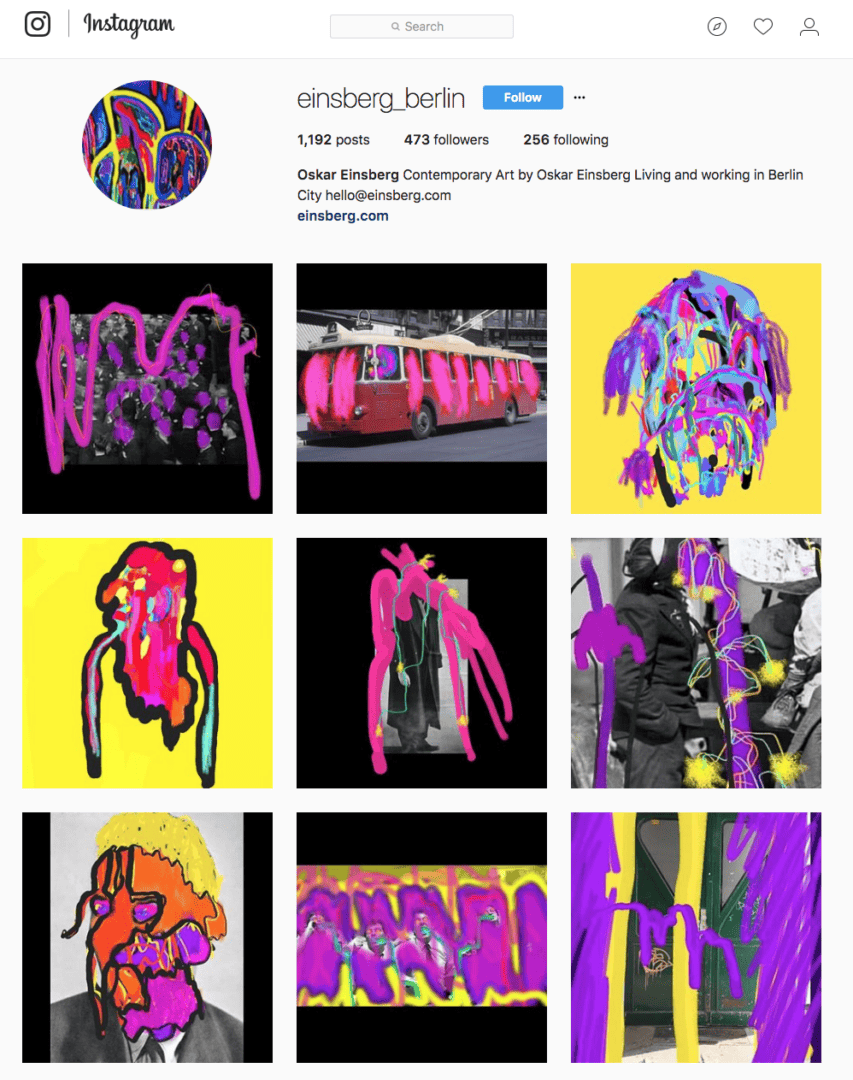

Instagram feed of artist Oskar Einsberg | @einsberg_berlin

In a passing glance of Einsberg’s Instagram, you can see what Saltz is referring too. There’s a repetition of color and digital scribble over found and self-created photo, but that comment is criticism alone and with it not much action can be taken from the artist’s perspective. The brisk nature of Saltz’s comment is easily grasped — he is critiquing via a mobile app and with over 282,000 followers, a fully realized response is not permissible by virtue of time alone, but criticism without the goal of being that outsider voice in search of the artist’s truth, unfortunately, is of no use and fully negative, with the artist’s only recourse to either ignore it or toil with that shard of criticism with no understanding of what the critic saw that they themselves did not.

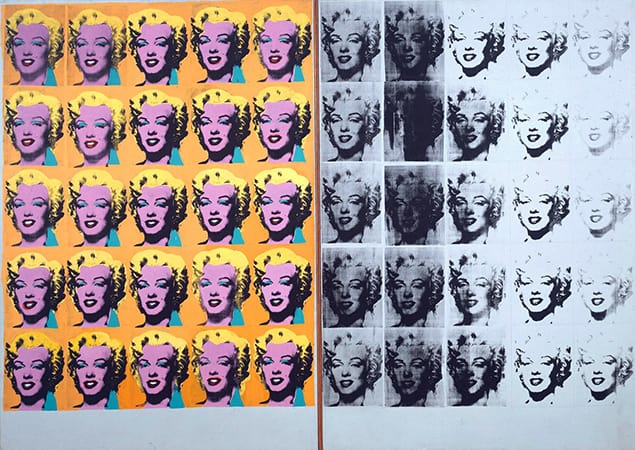

I do agree with Mr. Saltz, a critic is free to write whatever they think, be it positive or negative, but I would add, it must also be constructive. The comment, ‘Your work is much too repetitive’ is an opening line to a larger essay. Repetition itself is not a sign of failed art. Warhol used it effectively throughout his career as a way to comment on the manufacturing quality of pop culture and also the aspect of deterioration itself — in ‘Marilyn Diptych,’ the repeated image of Marilyn Monroe slowly erodes with each copy, yet even the most damaged iteration is still obviously Marilyn. Nothing could fully erase her celebrity. Composer Steve Reich took repetition to create compelling musical compositions. There is repetition, and there is redundancy, which may be Saltz’s aim with his comment.

‘Marilyn Diptych’ (1962) by Andy Warhol

Oskar Einsberg establishes the repetitive nature of their work through color (yellow and purple), device (digital ink), and canvas (found image), now, all Einsberg needs is to find a purpose for it. What is the repetition for? Is it vital? If not, leave it behind. What part of the sequence of images keeps them coming back to the manipulation of photographs? Is there a reason for the loose doodles themselves? Would it change the work if Einsberg took all the photos as voyeur or as a choreographed scene, or perhaps drew or painted new images? What does this specific set of repetitive elements speak to? If repetition leads to redundancy, that leads to becoming pointless, so is the sheer volume of the repeated idea the artistic statement? Saltz’s comment (and Einsberg’s work) leave more questions than answers.

I spent years writing critically about the work of other writers and the bulk of the first draft of these critiques was predominately negative. The analysis would be finalized after repeated readings of the work to seek out any sign of purpose, or moment where the artist lost their path, to act as an anchor of the critique. That was the base of my analysis — synopsis ( here is what you wrote), structured notes on the elements of the story (here is what I read), and a final critique addressing the piece as a whole (here is what worked, what didn’t, and why). Saltz’s Instagram post was aimed at art writers, accusing the positive reviews on weakness, perhaps laziness, and I would agree that these types of reviews help no one. A review of a gallery exhibit or profile on an artist that is positive but not informative is not of any use. “I like it and you will too,” doesn’t even work as an approach to inspire an audience to join in on the conversation.

Saltz is a gifted and insightful critic and his post made me evaluate what the exact purpose of my own art writing is, and question whether the perspective I take is of any benefit. I keep a notebook, a list of names and ideas, and ask myself a series of questions before writing anything —

Q: Do I like the art?

A: If not, why have I been thinking about it? What made it stick in my brain?

Q: Do I have the language to explain why I like it?

A: Writing about what you dislike comes rather easily. Writing about what you like and why it affects you, without praising in generalities, takes a bit more thought and can be quite difficult. It begs more questions — do I feel the work is good, but don’t have a proper frame of reference to speak from? This happens. Comic books and collectibles have a deep history I haven’t fully absorbed.

Q: Has it been written about before, and if so, do I have anything new to add?

A: Plenty of art, illustration, and their creators have been written about countless times and I don’t want to clutter the world with more of the same. If an artist has been written about well, I don’t need to touch it, unless I feel like I have something to say that hasn’t been spoken of.

In an article for HOW, I wrote about illustrator Martin Ansin. Ansin called the article too positive, suggesting I add something negative to balance it out. It was a comment I wrestled with — the only negative comment I could make about his work is that at times his work was far better than the subject matter he was illustrating, which, in an industry of art directors, clients, and brands, is far too common. Mr. Saltz’s post addresses quite a bit at once, reminding me why I have always dodged the labels of critic and journalist, opting to call myself a cheerleader, but perhaps I have failed by not embracing the constructive criticism that I value receiving on my own work. The illustrator has the art director and the client giving them comments at each step — the critique begins at the hiring and ends with the paycheck, which could speak to the importance of criticism in fine art, where there is nowhere to get honest feedback. Cheerleading is fundamentally positive, but the reader does not see all that is not written about, and in that silence may be my own criticism.

I was in an art group where insulting other’s work was celebrated as free speech. Their free speech didn’t involve my voice though, which simply demanded that if you take the time to insult artwork, IN AN ART GROUP, that could maybe at least include a why you dislike something? Because otherwise I could post ANYWHERE. Apparently that was way to demanding and constructive criticism was a concept too simple to be true in the eyes of the admins. I must be secretly wanting compliments only. A “nice” is just as unhelpful as a “crap” when it lacks the why, but ok, it’s more fun lecturing me on stances I don’t even hold or never even promoted. But explaining my stance was pointless. These people were eager like vultures. I had more problems with the group, than with the guy who thought his tastes could dictate my work. I even told him, I don’t want to or need to change his taste/opinion and he seemed to accept that he had no authorative argument when tastes simply differ. The rest still focused on projecting their complexes onto me or telling me, I was being too “personal”. Obviously they all agreed my drawing experiments deserved to be called shit, because the guy who go’s around calling people’s work literally “shit” somehow was not being too personal. And with projecting complexes I mean a lady, that randomly chimed in to accuse me of finding my drawings superior to her work. That was so out of nowhere and unreal, I was busy explaining constructive criticism and never made the actual quality of my work even a point. I was not in the delusion I could force people to like my stuff. So, 0% reading comprehension, 100% projection of their own issues.

In the end I was banned, but not much was lost to me. I study illustration and people pay me money to paint for them. I don’t need validation from bitter old hags that are confused by a graphics tablet. It’s just scary and upsetting – I mean obviously, since I wrote a whole salty paragraph – how eager some people are in making you a target when you don’t want to gulp down their shit treatment and question their intentions and priorities. It made me loose faith in common sense. I have stopped expecting reason from other’s. Give calm constructive criticism and it’s taken like insult, get textbook insults and have it being sold as “constructive”. This part of the art world is a wild mess. Everyone’s at a different level of understanding what good criticism is made of and that it’s actually very enlightening and interesting and can enrich your work so much. I’m tired of correcting people on their misconceptions, but you can’t escape being a victim to them. Still learning how to handle this and I guess ignoring is the most productive solution.