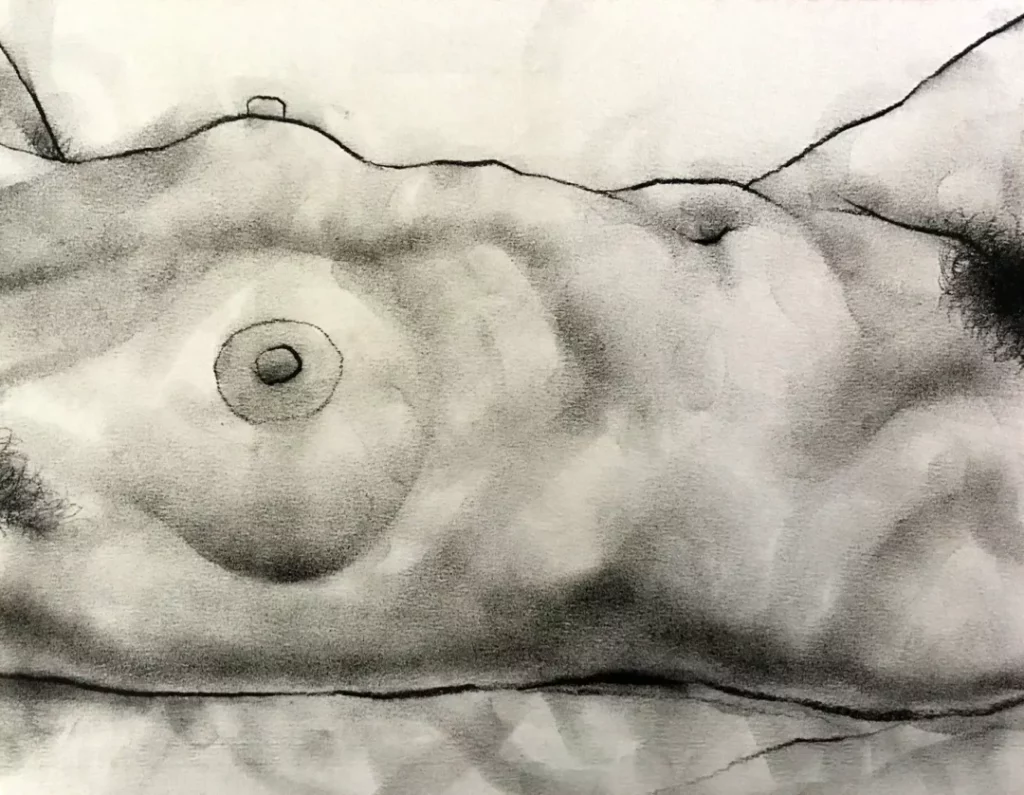

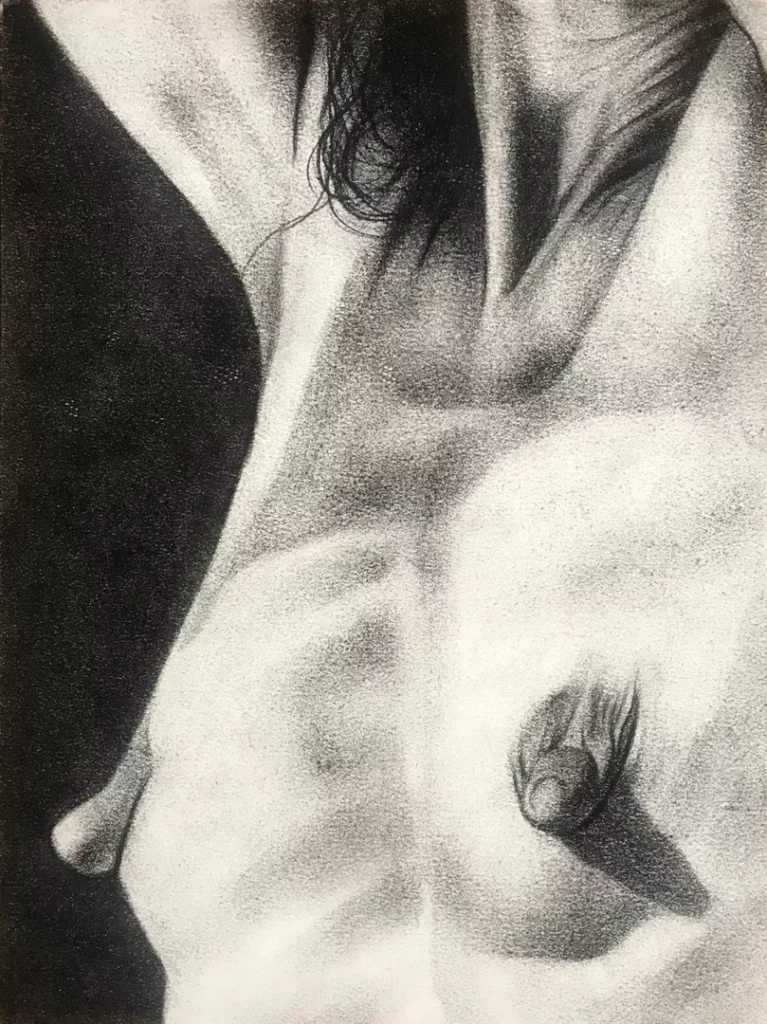

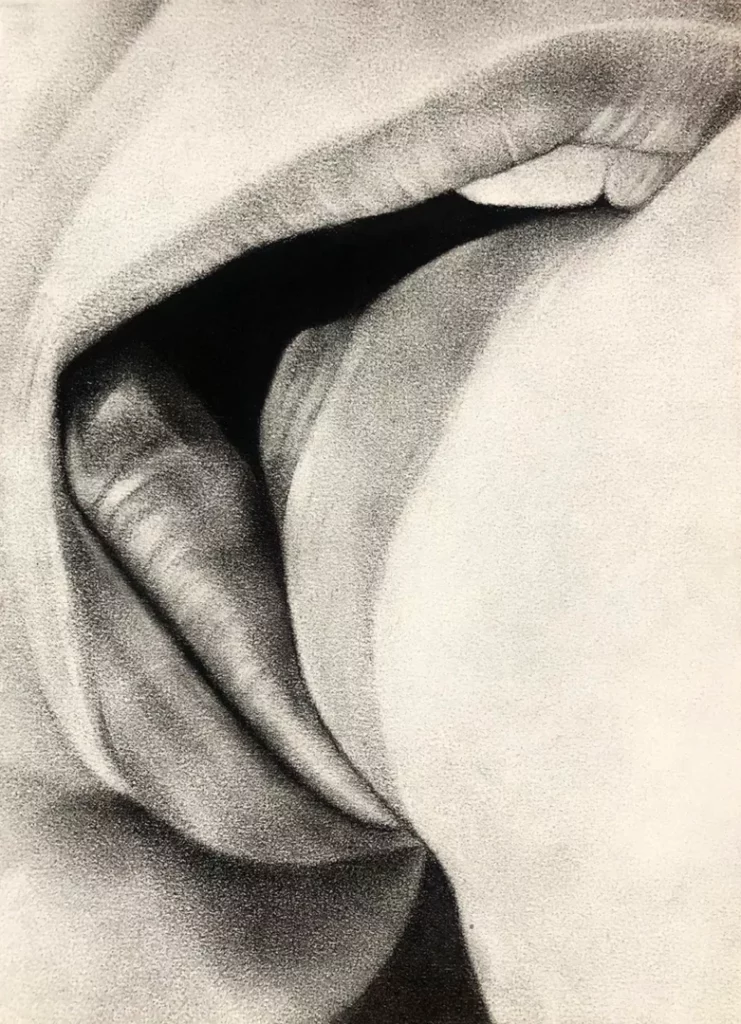

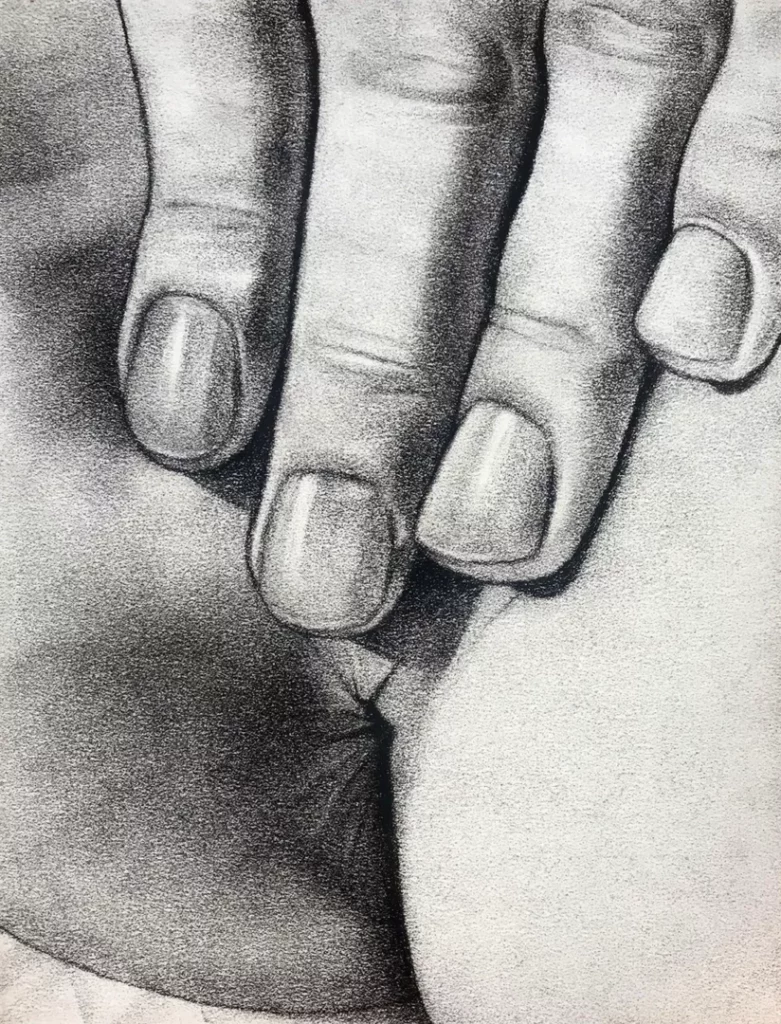

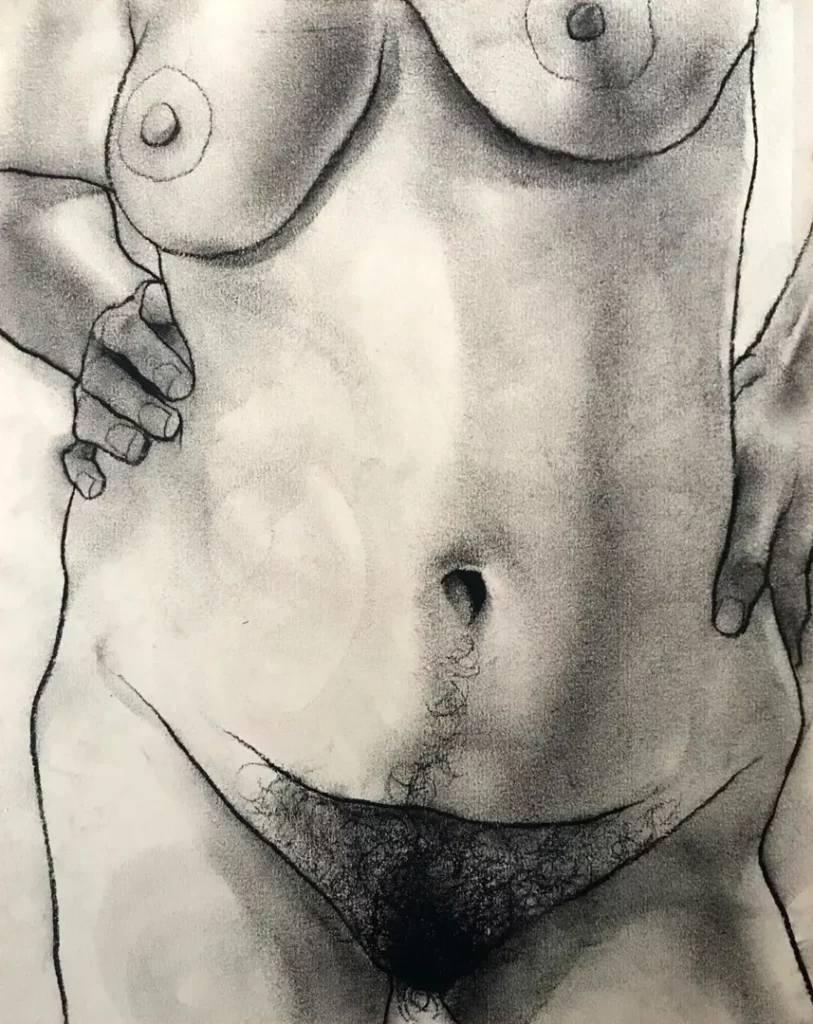

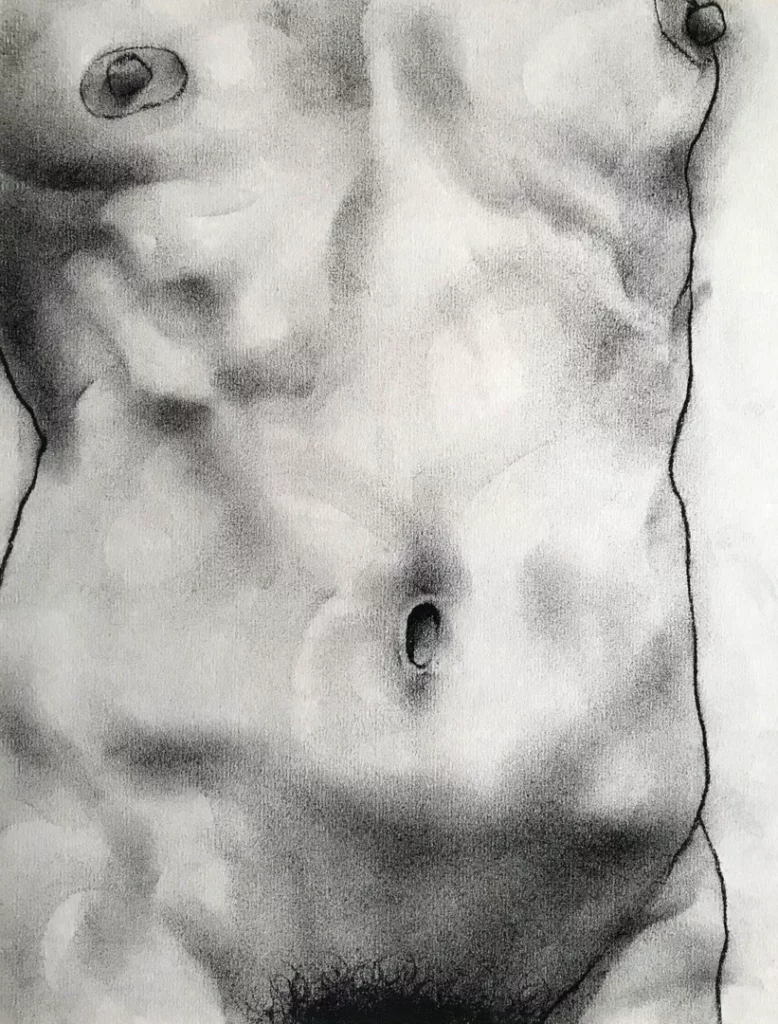

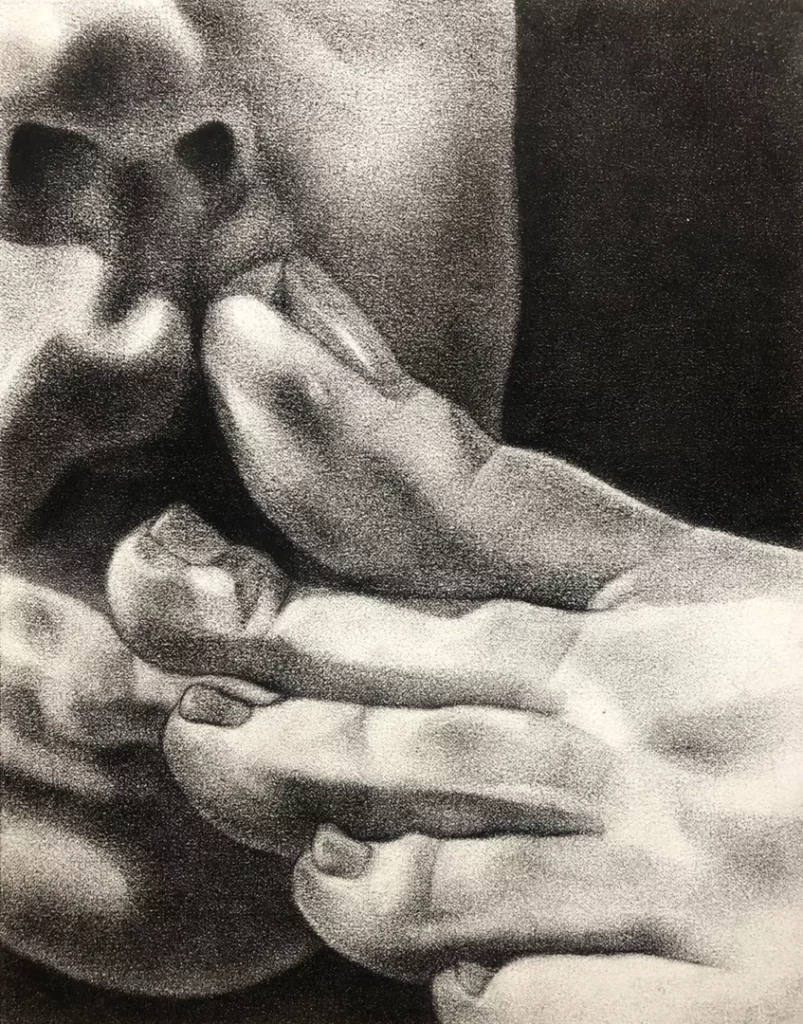

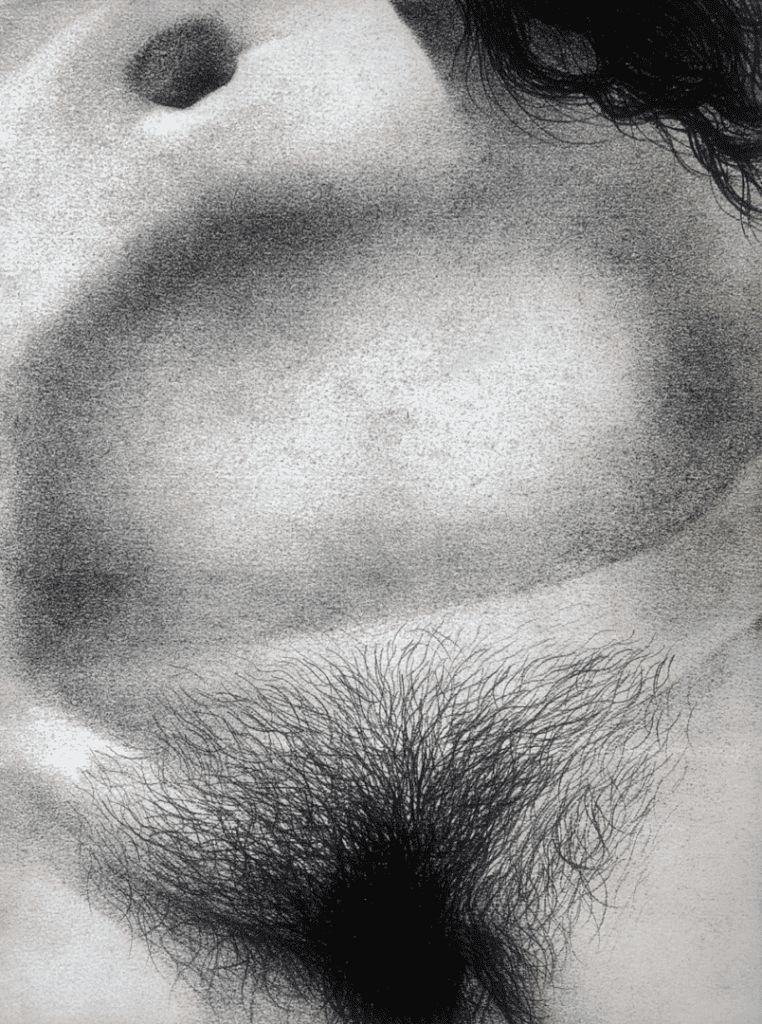

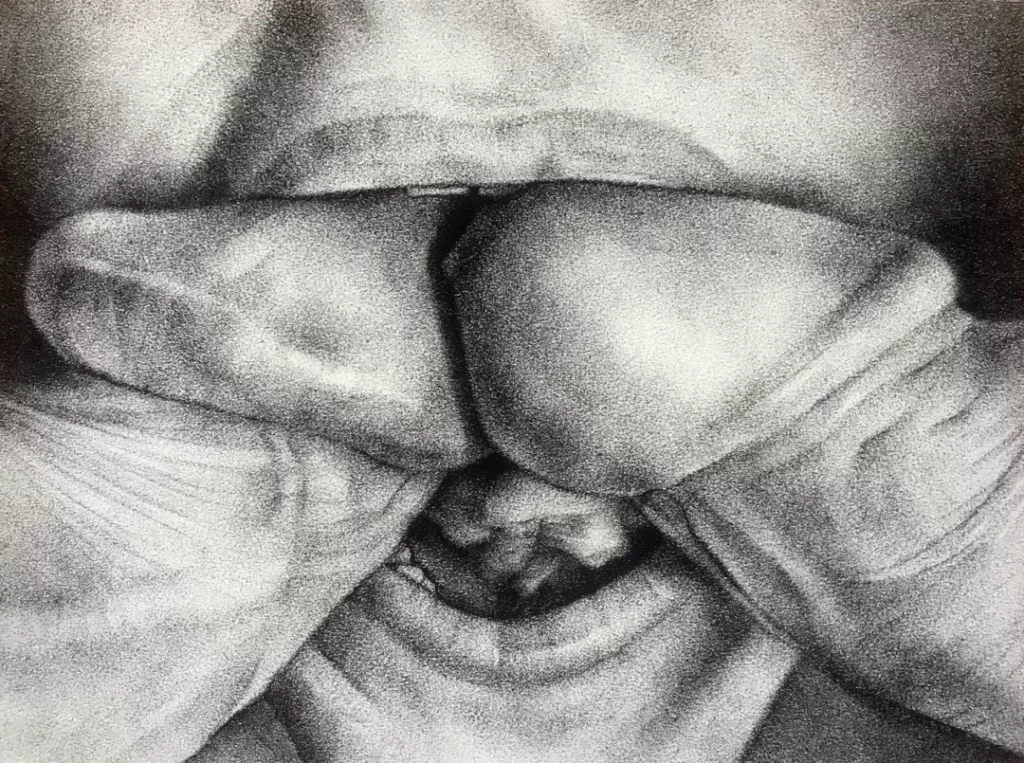

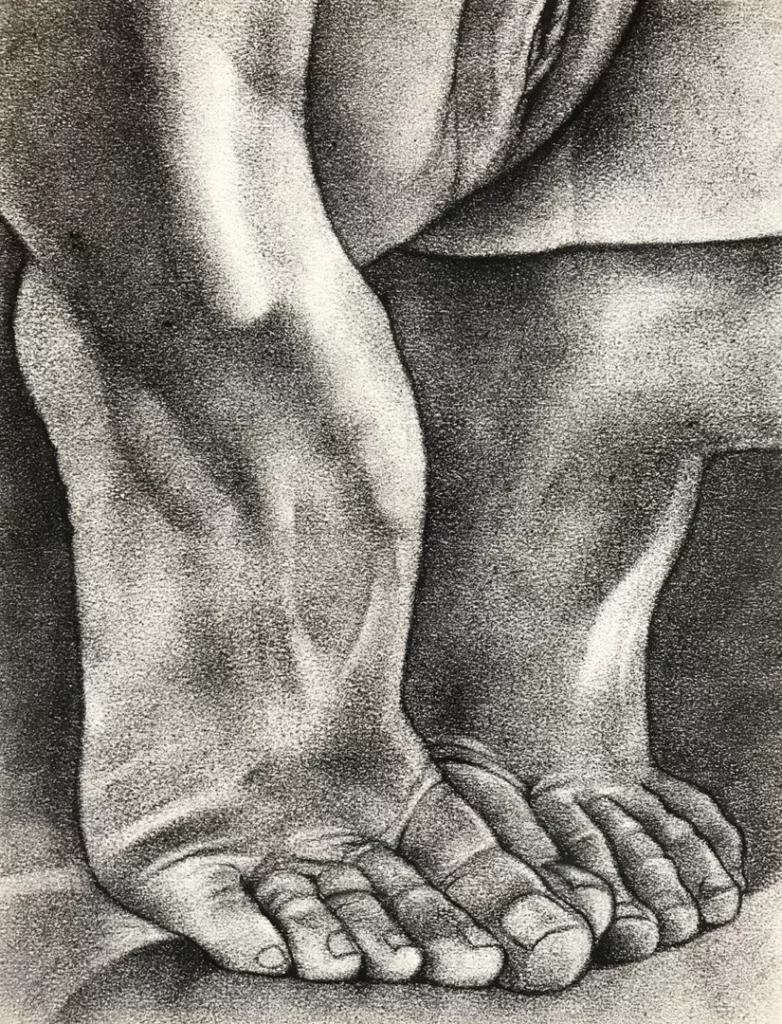

In the figurative work of artist Phillip Dvorak you will find understanding of flesh and fat, muscle and the rounding of light. He is an observer and participant in each drawing. The eroticism Dvorak commits to charcoal and paper contains the sweet tension of the voyeur. His drawings bring the body close to you — relaxed and composed.

Dvorak’s drawings are an exploration of the human form in all of its subtle charms and tenderness, suspended in time. These bodies are like our own. Unique. Imperfect.

Untitled (Female Nude) by Phillip Dvorak

CJ: On Instagram you shared a drawing of when you were thinking about fashion illustration, but overall, you focus on macro-scale body portraits. Have you always been drawn to figurative work?

PD: I suppose to some degree, there’s always been a bit of the figure present in my work—even the abstract pieces I was doing for a while were based somewhat on the figure. As a kid I loved doing portraits—I guess that’s where my love of the human form began.

Untitled (La Beauté Erotique De A ) by Phillip Dvorak

On your Instagram you will often sprinkle in photographs of your model. I was curious how you find your models? Do you prefer to work with the same models, or do you like what a variety of shapes and sizes can offer?

I definitely like working with a variety of models. I find many different body types exciting and inspiring, though I suppose I’m more drawn to some than others. While living in San Francisco I was able to attend lots of different drawing groups and was exposed to a wide range of models—it was heaven!

At times I would hire my own models for specific projects, and often talked friends into modeling. Many models were happy to trade their time for a drawing—that’s a nice arrangement. Now that I’m in Maine full-time my access to models and drawing groups is more limited, but I can still find inspiration. I run a drawing group for a local arts organization, and many of the models are from a local college.

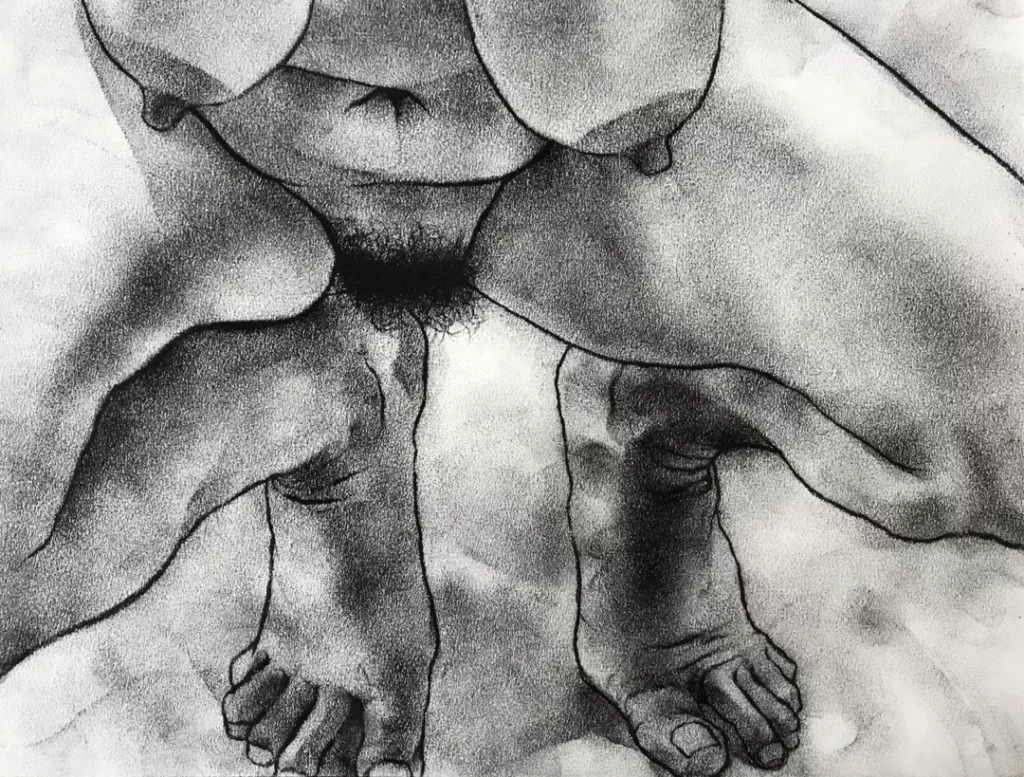

Untitled (Réunion) by Phillip Dvorak

Are you mostly drawing live models, or from reference photos? Curious on your approach and if you have ideas for compositions to guide the process?

I love drawing from live models when I can, but often end up working from photographs. There are pros and cons to both approaches. The focus and energy involved in working with a model for a specified period of time is exciting and challenging—I really love it. Working from photos is very different—there’s no time limit, so much more detail can be achieved.

During Covid I began working from photographs and my imagination much more and found I enjoyed it. I try to work from my own photos as much as possible, but find I’m often drawn to other existing images as well. I began to focus more on tightly cropped, erotic imagery—stuff that would be difficult with a live model.

How much are you directing your models?

I’ve never been very good at directing models—maybe subtle things, but I mostly wait and see what happens. With photos I can search for possible ideas and go from there.

Untitled (La Rencontre) by Phillip Dvorak

Untitled (Felicity) by Phillip Dvorak

You’ve made the move from the west coast to the east coast. Has relocating from the San Francisco area to Maine changed your work, or your outlook on your work? Does the growth of the work / craft move in different settings? Inspirations change?

It’s changed in that I draw far less from live models and more from my imagination and photographs. My work has always had an element of the erotic in it, but I think (surprisingly) it has become more erotic since moving from San Francisco to Maine.

Maybe it’s the isolation that has allowed me to feel more freedom. The problem, of course, is that there is a much smaller market for—and acceptance of—erotic pictures here than in San Francisco. I really don’t have anywhere here to exhibit my work.

Untitled (Female Nude) by Phillip Dvorak

Untitled (Female Nude) by Phillip Dvorak

The rise of social media has made sharing art incredibly easy, but I still see artists with nudity in their work being shadow banned or just banned altogether. A door opened, but not equally for all niches. With mainstream media being of little help in advancing erotic art, how have you grown your audience over the years? Do you have a core group of collectors and galleries that you work with?

Social media has been great for allowing me to reach a much larger audience than was ever possible with more traditional ways of showing work, but unfortunately most sites have really cracked down on erotic work. It’s become quite difficult to comfortably share my work on Instagram—I’ve already had one account (with 37K followers) abruptly deleted, and I’m continually getting warnings on my new account.

I know there’s a big market for erotic art—I was selling quite a bit online a few years ago, before all the censorship started—it’s just a matter of getting it seen and made available to potential collectors. I love pushing the limits and doing very strange and sexy stuff but I find myself toning it down so it doesn’t get censored. It’s unfortunate that social media is in a position to dictate the kind of work artists make, but I think that happening to a lot of us.

Untitled Nude (Z) by Phillip Dvorak

Art depicting genitalia and other unseen / unshared parts of body often get the label of erotica. That label, or genre I guess, gets pushed to the side, going underground even in our modern world of social media and the internet. Is the erotica label something you think about, or perhaps aim for?

Definitely—I fully embrace the term. I don’t think there should be anything shameful about erotica. I do need to be careful when sharing on social media, where “erotica” is taboo, but I try not to let that affect what I do.

I love all forms of erotica—art and literature. And, in a way, I’m actually enjoying the challenge of creating erotic art that can get past the social media censors. It’s making for some very interesting work.

Untitled (Désirer) by Phillip Dvorak

Missy III by Phillip Dvorak

You rarely draw faces, but it is a joy when you do. They have a loose Schiele-like expressiveness that a drawing of something like a woman’s backside won’t have. Do you approach the drawing of a face differently than another body part?

Drawing faces is a challenge, especially if you’re really trying to capture a likeness of the sitter. I enjoy it very much though, and even though it’s more complex than most parts of the body, I approach it the same way.

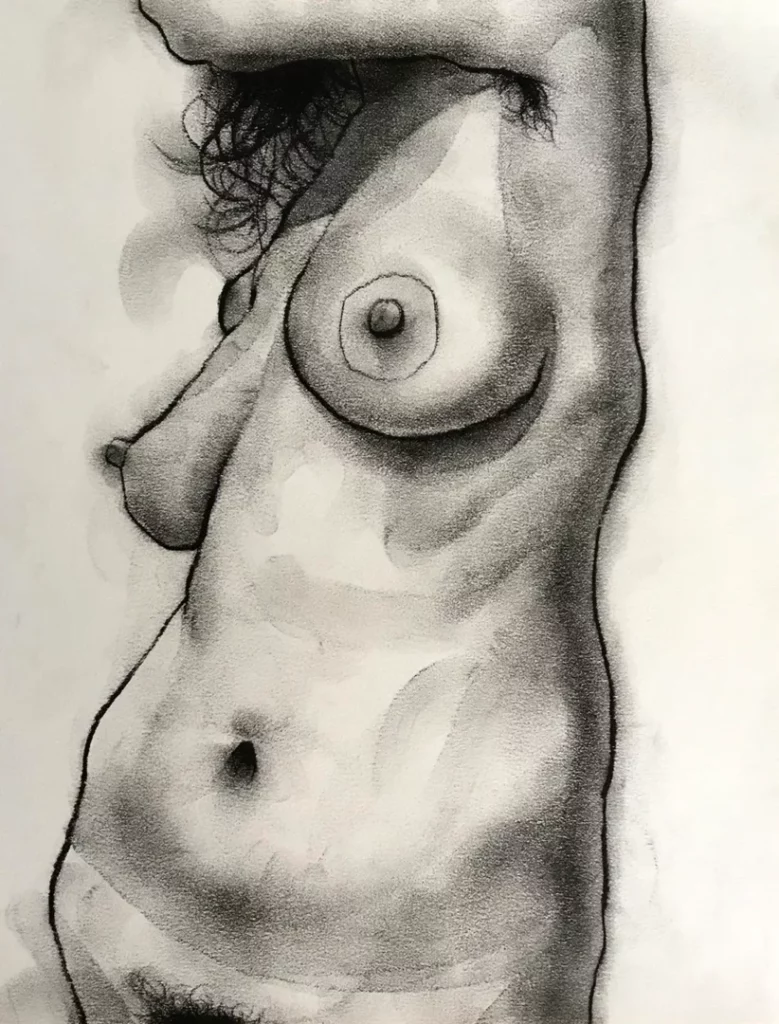

Untitled (Le jardin luxuriant) by Phillip Dvorak

There is a magic to your approach to shading, especially the subtle shifts in light and flesh. I think of your drawing Untitled (Le jardin luxuriant) and the rich black of her pubic hair and the perfect indents at the hips. There is so much going on, so much for the eye to take in, yet you never take us out the reality of it in order for the drawing to be interesting. The focus on realism against the almost unreal craft really enhances the feeling of magic for me.

It’s always sort of finding ways to combine the real and recognizable aspects of the figure with something more abstract and stylized. I try to remember that the drawing exists independently in the world—that it’s something unto itself and needn’t be strictly dependent on the source. I used to do a lot more work that was completely imagined—no reference material at all—and I’m working to bring a bit more of that spirit into my work.

Untitled (Bisous) by Phillip Dvorak

I own two of your drawings and have sat with them, trying to see the how of what you do. The contour lines are there, then the graphite ebbs and flows, the tool seemingly never lifting off the paper. I try to draw daily, and I always tend to start from the eye or nostril. The darkest facial feature and work from there. Do you have a process that you like to follow; start at x, then y, etc.?

When I’m working with a model, I always take a moment at the start of the pose to really look closely and decide what part of the gesture I find most intriguing. It could be any part of the body—it just needs to be interesting and create a good composition. Once I decide on a portion of the figure to draw, I’ll just start in with the line work—maybe starting with more complex parts first and working out from there.

A lot of the poses are 20 minutes, so it’s important to plan ahead a bit and know how detailed you can get with certain parts of the drawing. It’s always a challenge and that’s one of the things I love about working with a live model. When working with a photograph, one has the luxury of time. I still try to crop and find the most interesting parts to draw, but my approach is different. I tend to smudge more at the start, sort of “find” the composition that way—gradually filling in.

Untitled (Fortune) by Phillip Dvorak

Untitled by Phillip Dvorak

With doing figurative work for so long, are you able to “see” the final drawing before you even start, or is it a surprise each time?

I suppose I kind of imagine what it will end up like, but I really try to keep the element of chance in the drawing. I like being surprised by how it turns out.

Untitled (L ) by Phillip Dvorak

If I’m not mistaken, you and your wife own a farm in Maine. I envision an idyllic existence of drawing, moving some soil around, drawing some more, and enjoying time with your wife. I was curious about the life you lead, the meat and potatoes of it. The art you create evokes patience and calm – they are meditative. Peace inducing. That macro perspective takes the focus off the individual, the self each of us lives with. Your drawings depict life itself. Do you see yourself in your work? Your beliefs and outlook?

It’s actually a flower farm and has evolved into a floral design business as well. We have about three acres of beautiful land in rural Maine, close to the ocean. It’s peaceful, but a lot of work! Seeding, planting, growing, harvesting, making bouquets and arrangements—it gets crazy at times. In winter things slow down, of course, but there’s still a surprising amount to be done. I try to keep a balance between all the farm work and studio time, but it’s not always easy. I know how important it is for my sanity to get into my studio enough, so I try to make sure I do.

We moved to Maine full-time about three years ago, after about 15 years of splitting time between Maine and San Francisco. We’re both California natives, so the move to Maine has been a big change and huge learning experience. I had been in San Francisco for about 25 years, so being suddenly in rural Maine full-time is quite an adjustment. I wasn’t nearly as ready to leave SF as Lee was, and I do very much miss friends and family and many things about California. But overall, it’s been a good change.

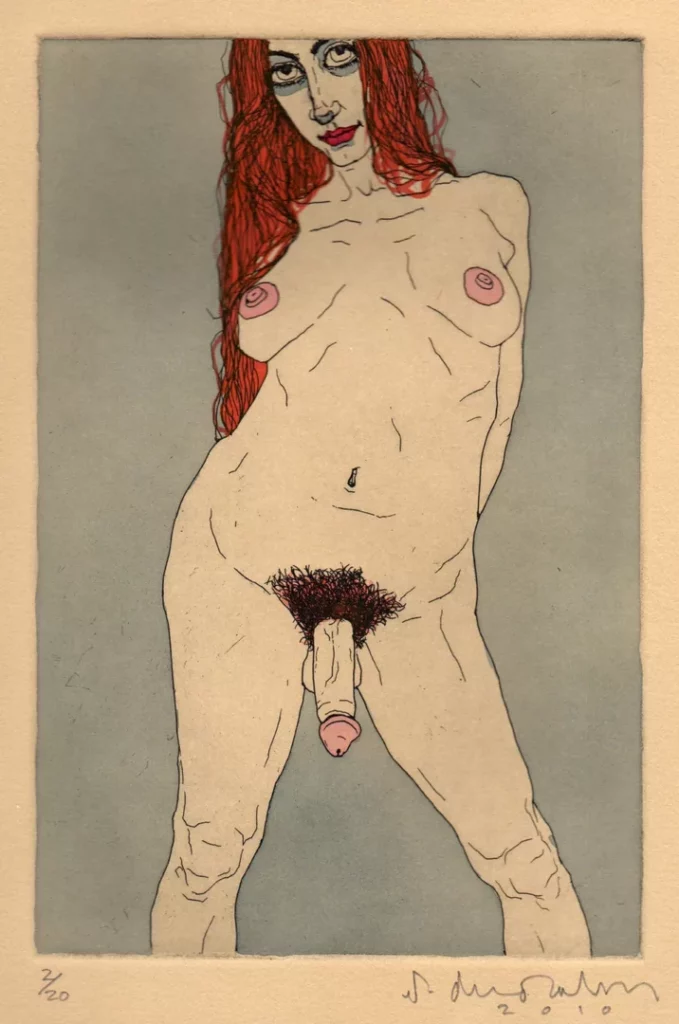

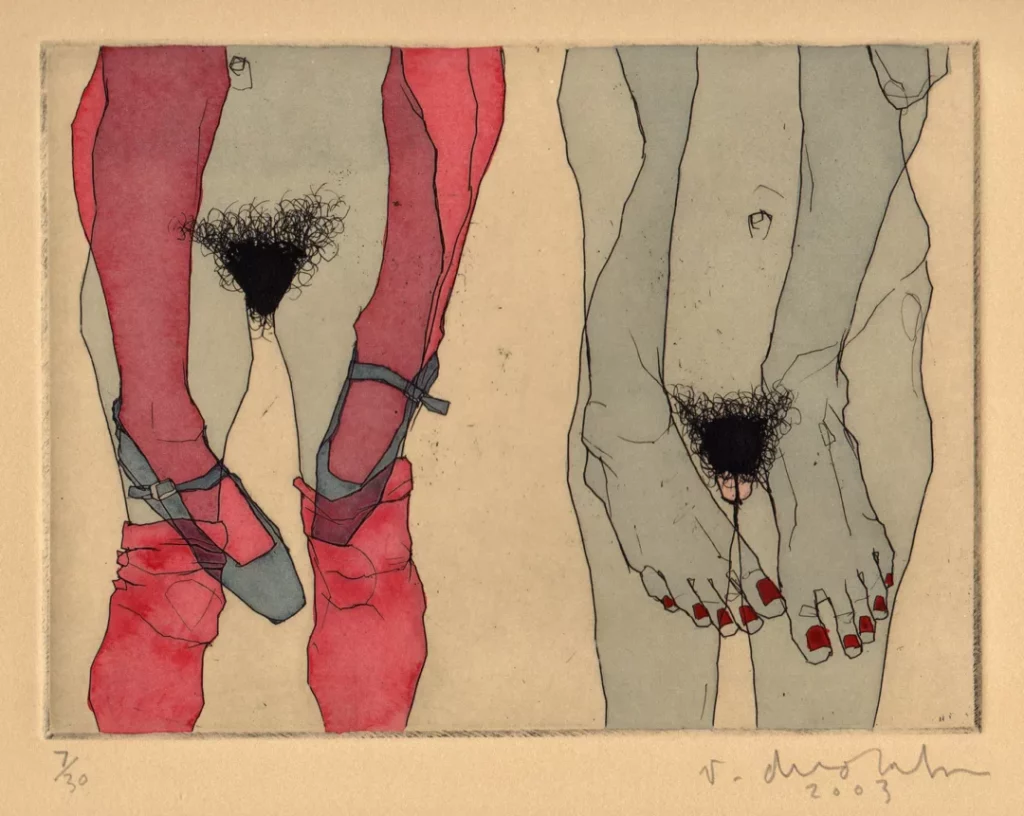

You’ve created a wealth of etchings. The lines are incredibly sharp and clean – were these prints dry point or was acid etching involved?

The etchings are line etchings using hard ground and an acid bath. I’ve done some dry point, lithography, and a few other forms of printmaking, but most are the hard ground line etchings. I then hand-color each print using watercolor and gouache. I like combining the looseness of watercolor with the “mechanical” feel of the etching process.

Back To Marseilles by Phillip Dvorak

I did quite a bit of etching in my past, and it changed the way I looked at drawing the figure. Getting the forms right without the softness of shading. Mistakes in my drawings became way more apparent when burned into a zinc plate. I was curious if there was something that etching brought to your art that wasn’t there before?

I would very carefully make the drawing ahead of the actual etching process. As you know, by the time you start putting down the lines on the plate, you’ve put a lot of time and effort into it—you don’t want to make any mistakes if you can help it!

I would lay the drawing over the plate and make tiny pinhole marks through the paper onto the plate—I’d then have sort of a guide of marked out dots to help create the drawing on the plate. So yes, it was a very different way of working—much more preconceived and planned out than I’d ever done before.

Also, I was creating images that were based on a combination of a variety of reference sources—my own photos, found images, imagined images. That was new, as well. Once or twice, I did try to do a quick figure drawing from a live model on a prepared plate, but it never worked out all that well.