The woman takes a bath. There are other women there with her — her servants, there to bathe her. She is outside. A brisk evening, sun dropping. Another windless day in the desert ends. Her husband, a loyal soldier, has yet to return home from the battlefield.

From a distant balcony, a stranger watches.

Thus begins the story of Bathsheba and King David, which is told in 2 Samuel 11 of the Hebrew Bible. As a piece of writing the story is quite straight forward. Simple lines of action devoid of emotion and reason.

King David watches Bathsheba bathe and sends for her. He takes her and later finds out she is pregnant from their meeting. In order to hide that he is the father, the King calls Bathsheba’s husband Uriah from battle and tells him he can go home, in the hopes that he will get intimate with his wife and later assume he is the father of the unborn. Uriah refuses to abandon his fellow soldiers, so the King devises another plan — have Uriah sent to the front lines of battle, where he will surely die.

With Uriah killed, David takes Bathsheba as his wife and when she gives birth to their child, it dies days later. Their next child, Solomon, does not fall victim to the same fate and succeeds David as King of Israel.

There are details left out of this summary but what we have here is the skeletal truth of the story and one that leads to a series of questions — Why didn’t Bathsheba speak up? Was she forcefully taken or a willful participant? Did David fully expect a loyal soldier such as Uriah to defy the laws and leave his battalion behind? Is there a hero in all of this? Does there need to be? It becomes a story on perspective and interpretation.

As a character Bathsheba has been portrayed through countless lenses — changing with each artist, evolving with each time period. Bathsheba is strong, she is frail. Loyal. Weak. Submissive. Proud. Bored. A predator. She, at one point in time, has been everything mankind could imagine.

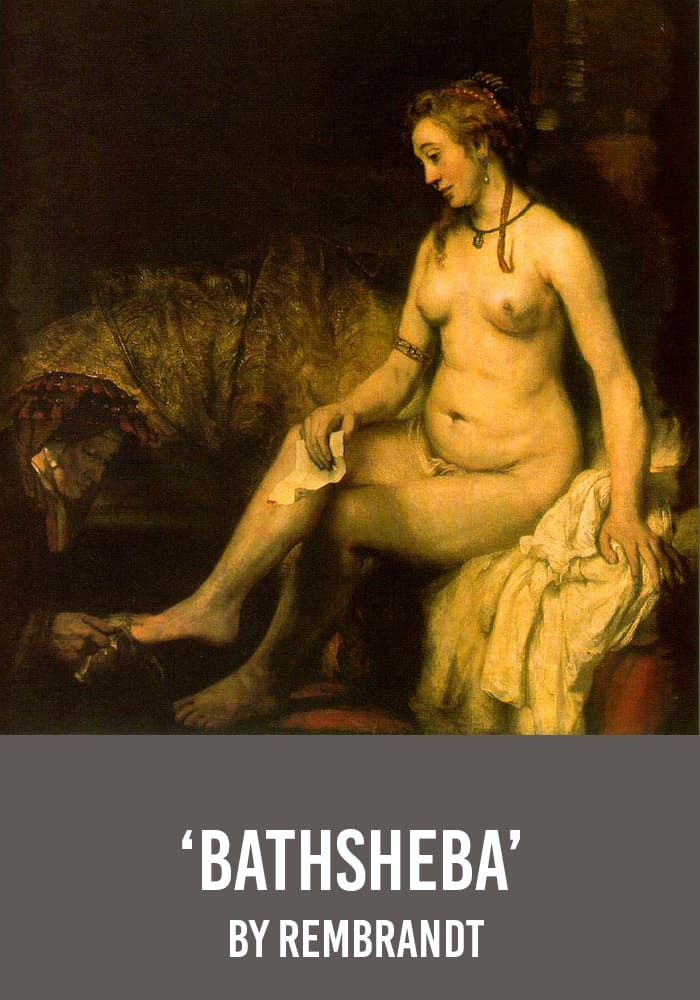

In the hands of Rembrandt Bathsheba is plump and warm; motherly. Inviting. In her hand is the letter from King David, making his intentions clear. There’s worry and concern on her face — the look of someone who knows what they are required to do, aware of the consequences. That look she gives her handmaiden, the older woman tending to her feet — she relates. They have the same role in society, she’s just higher up the social ladder.

Rembrandt shows us an intelligent woman facing a request she knows will only bring bad things.

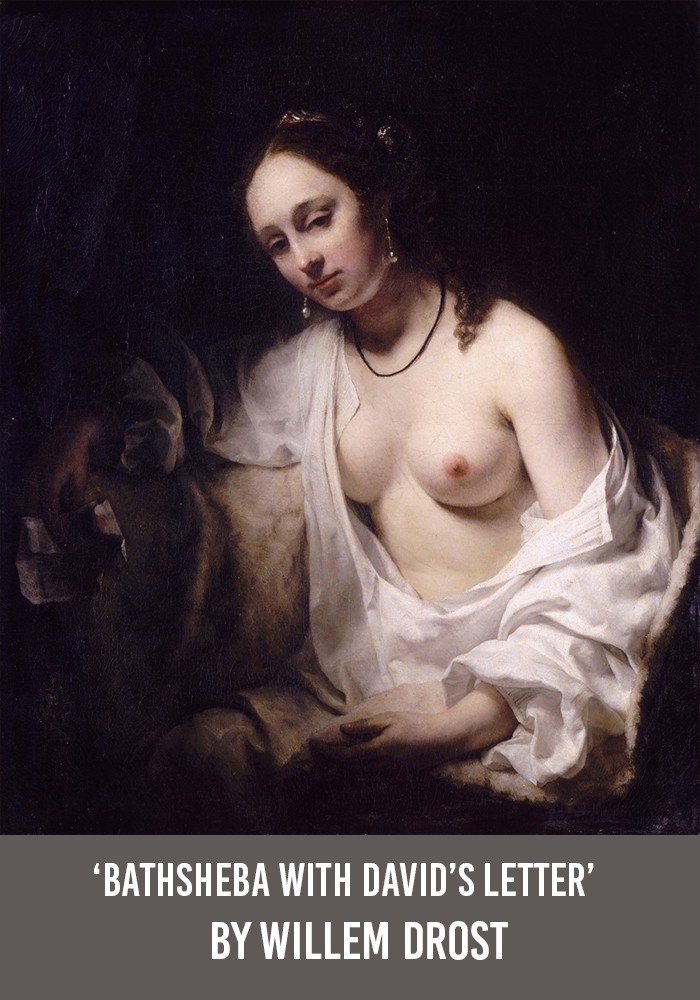

Willem Drost was an apprentice to Rembrandt and his version of Bathsheba can be seen as a calculated response to Rembrandt’s painting done in the same year.

Drost’s Bathsheba holds the letter where she just learned that she has been requested by King David. She knows what this means. The viewer knows she is beautiful and this version of Bathsheba does as well. There is a sense that this isn’t the first proposition she’s received while her husband has been away, but it might be the first she cannot refuse.

Her face is a vacant mask — emptying her body of herself, perhaps the King can take her physically, but he cannot have what makes her her.

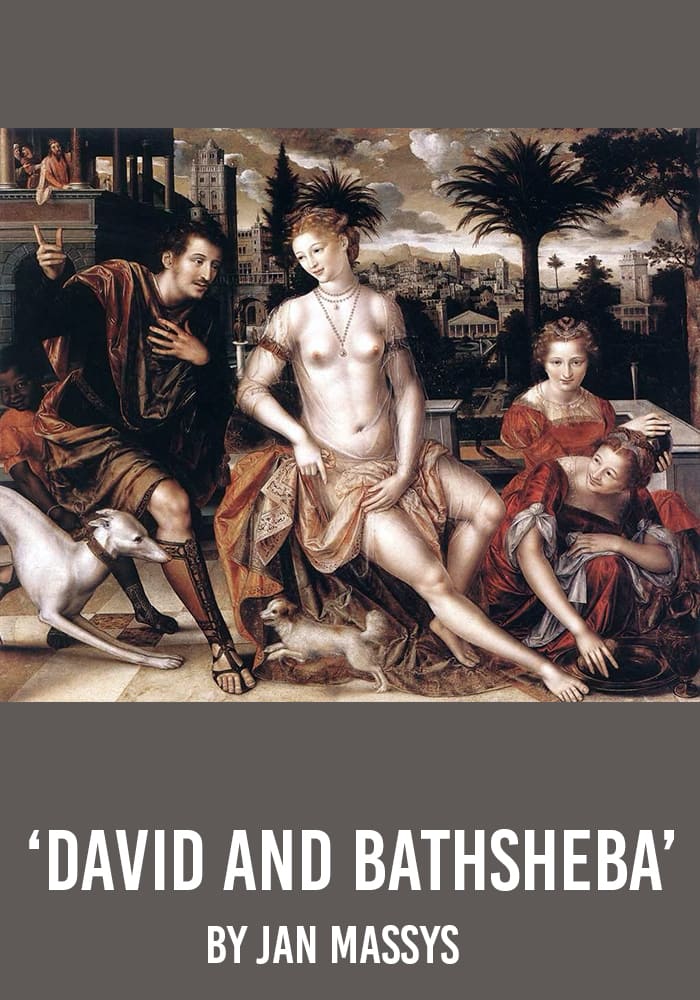

Jan Massys‘ 1562 painting ‘David and Bathsheba’ looks at the moment the King’s messenger informs Bathsheba of the request, as the King looks on. Massys shows us the moment as just another good day in the kingdom — the front-most handmaid looks pleased to hear that her Lady is desired by the King, and Bathsheba is quite pleased herself.

There is joy here, except in the face of the handmaid in the back. She stares directly at the viewer, a smirk she shares with the combative dog at Bathsheba’s side that belies the superficial innocence of the scene.

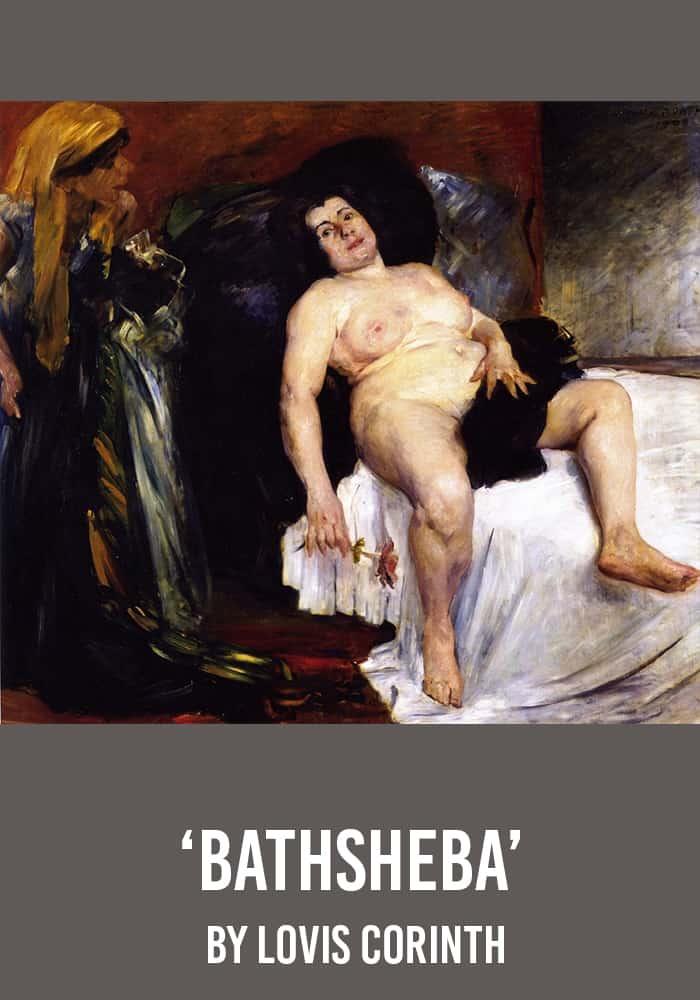

In 1908 German painter Lovis Corinth did his version of ‘Bathsheba,’ a painting that reads like a bedroom Polaroid found in an abandoned box of junk. A token from a forgotten lover. For however bold the appearance Corinth’s Bathsheba can’t hide her modesty — a towel tossed in her lap hides most of her pubic area. She attempts a beautified pose, but the flower in her hand is more everyday weed than opulent rose. The handmaid at her side looks on, taking one last look at the stage she set for the King. This Bathsheba is more bored housewife than proper officer’s wife.

Corinth’s Bathsheba is the most realistic in terms of narrative — her gaze attempts to be inviting, but there’s an uncomfortable strain in her body. She’s a woman taking a new lover, unsure of herself and the moment. If one had to guess, she welcomes the affection of the King. Her husband Uriah has been away at battle for some time now, and maybe Bathsheba just wants to be desired again. To feel adored again.

In the 1800s Italian painter Francesco Hayez created a string of portraits of women — some Biblical in nature like his version of ‘Bathsheba,’ who he depicts sans letter and handmaidens. Hayez’s Bathsheba is a classic beauty. More sensual than religious, which makes sense giving Hayez’s penchant for painting odalisques and concubines.

Her hand dipped in to test the bath water, it’s as if the viewer has walked in on Bathsheba to give her the news, to tell her something she may have been hoping for. Perhaps bathing in the open was meant to entice the King, and here is her moment of truth. This Bathsheba is testing the water in more ways than one.

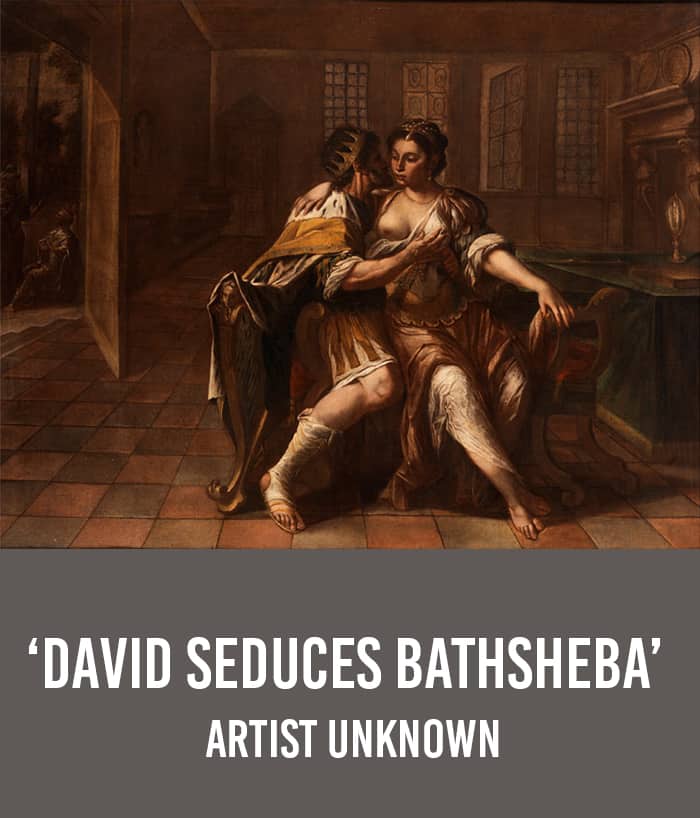

Depicting the act of David’s seduction is rare, but here we have the King mounting the sofa just to get close to a rather disinterested Bathsheba. The King is quite a bit smaller compared to Bathsheba, childlike in his attempt at an embrace.

The artist’s inclusion of David is almost to mock him, to say, ‘here’s a man that can’t get a woman any other way than by force.’ This Bathsheba is in complete control. You hope, maybe this time, things will work out for her.

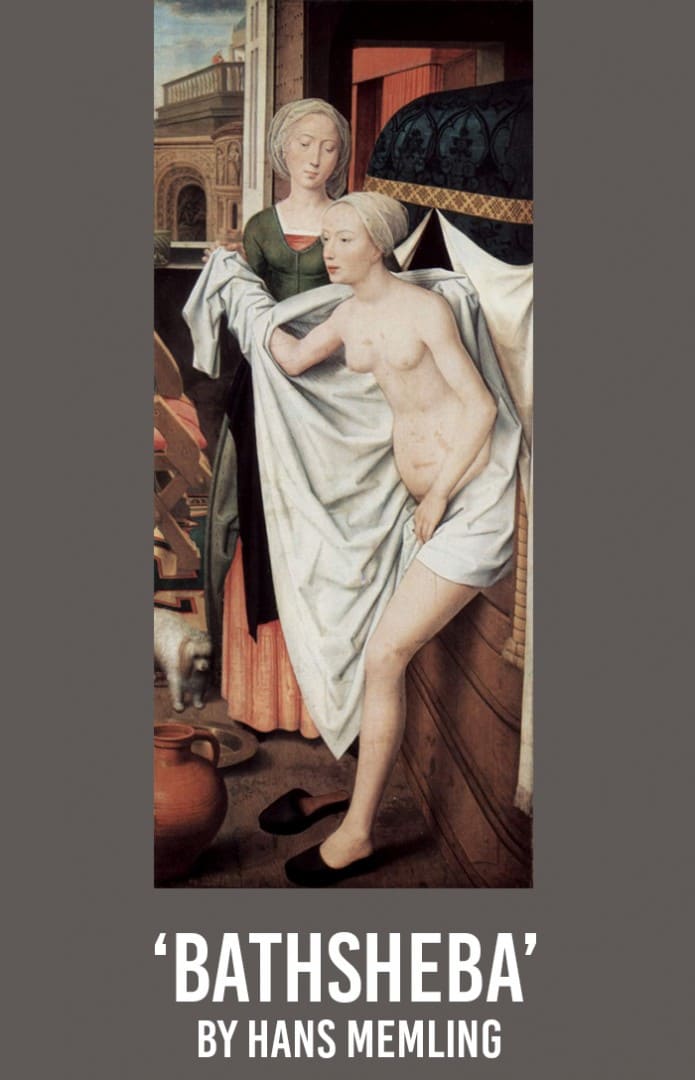

Flemish painter Hans Memling created his ‘Bathsheba’ in 1485. Pale and thin, her body is butterfly frail. She may be a product of his time, of his style.

Memling crowds the figures with vague structures, outdoors yet in hiding. Straight from the water to the robe. Modest. Memling makes no reference to the future of Bathsheba and her husband Uriah at the hands of King David, in fact, there is nothing specifically religious or even sexual about this portrayal.

This painting is cold and distant, or perhaps it is stoic and righteous. There’s an emptiness that can be seen as either the artist’s own temperament or his commentary on religion in art. Either way, Memling’s Bathsheba does not seem prepared for the pressure of the King and how her life is about to change.

Like Willem Drost, the Dutch painter Flinck Govert was also a student of Rembrandt and like Drost and Rembrandt, Govert instills his Bathsheba with a reflective quality — a woman mid-thought, caught in internal debate.

She’s more innocent than Rembrandt’s version. She may have the body of an adult but her face is child-like and her hair floats with the freshness of a newborn. Bathsheba is wistful, possibly looking forward to the excitement and rush that the King’s letter offers.

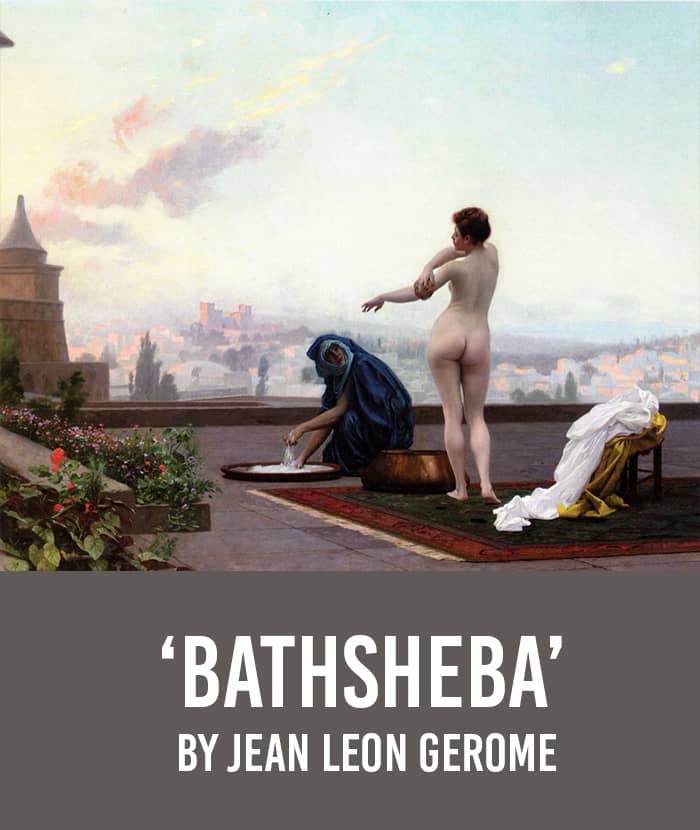

Jean Leon Gerome‘s 1889 painting of Bathsheba shows a carefree young woman enjoying the view of the city and fresh air on her skin. After a trip to Egypt and the North of Africa, Gerome’s work took in the influences from his travels and here, his Bathsheba fits inside that landscape.

This is not a woman with many worries, just simple pleasures — her feet comforted by a fancied rug, gorgeous flowers line the sill. She’s even chosen the perfect time of day to be outside. That sky, pink and yellow, soft and calming. Gerome’s Bathsheba fits in with his penchant for the female nude, and whether painting slaves, concubines, or a nude at the bath he always instilled the canvas with an aura of sensuality and eroticism.

Perhaps Gerome is guilty of focusing on the superficial beauty of a nude woman, and he’s not the first, but by turning his eye to the Biblical realm of the King David and Bathsheba story, he’s placed his figure in an odd light — with her husband gone to battle and living alone, this Bathsheba has no cares in the world. Her densely robed handmaid prepares the water and looks on. Gerome painted her under an unreal shadow while Bathsheba is a bright and glowing figure. His own comment on the roles of the two women.

This, all of it, might be the fate of her character. A symbol of the put upon woman for aggressive men. A righteous follower and believer. A sultry vixen or a prop, an excuse for nudity in art. She becomes more a reflection of the viewer than a being unto herself.